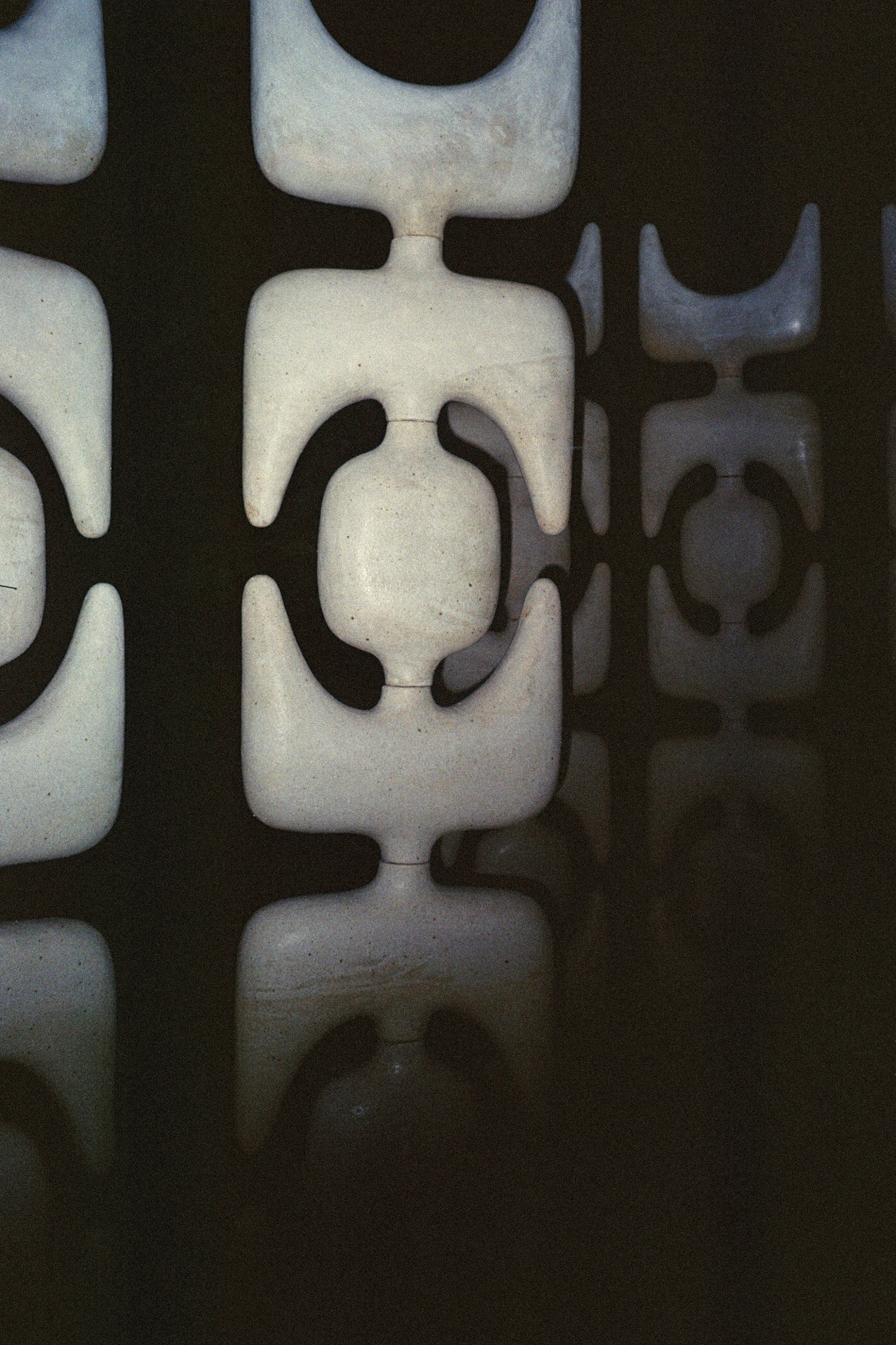

Trained at the Maison de la Céramique in Dieulefit, Natasha Dakhli quickly moved away from wheel-throwing, driven by a “visceral desire to create human-scale forms.” Positioned at the intersection of art and function, she delivers large, striking pieces—partition-totems made of interlocking modules, mirrors, or sculpture-like lamps—“objects that become part of daily life to spread a sense of quietness.”

Based in Saint-Victor-la-Coste, the visual artist learned to tune in to nature’s rhythm from her grandfather, a winemaker. The echoes of her native Algeria—cracked earth, mineral or sandy textures—infuse her creations, which evoke archaeological relics: “I want my objects to feel as though they were buried in the Mediterranean.”

In the same village, her neighbor, Marianne Langeberg, practices raku. She encouraged her to visit the Maison de la Céramique in Dieulefit. “I was completely won over by this school, located in the middle of a park with century-old trees, and by the richness of the teaching. That experience erased all my fears.” She bought herself a potter’s wheel and practiced alone in her basement, but continued working for a full year as a care assistant. Until the day she enrolled in a CAP (vocational qualification) in wheel-throwing, to gain the foundational skills needed for admission to Dieulefit.

The gallery owner Mélissa Paul discovered her on Instagram and purchased one of her first pieces. She later exhibited it at the PAD (Pavilion of Art and Design) fair in London, and then in Paris. That whirlwind of a first year gave her the confidence she needed, all while remaining deeply rooted in the small southern village that makes her proud. “The mistral wind, the warm air, the evening light, the dry, cracking earth, the moss, the lichen… I’m completely steeped in this environment,” explains Natasha Dakhli.

In perfect harmony with her surroundings, the ceramist wants her pieces to resemble ancient fossils: “I like it when you can’t tell how old they are. I treat my surfaces with very dry slips to achieve textures that seem weathered by time. I use a lot of layering—so much that it inevitably cracks.”

Straddling the line between earth, plant life, and mineral, her work also explores the relationship between lines and space: “I think of my pieces as architectural forms.” Why furniture? Because she wants to play with the boundary between the artistic and the utilitarian, the sculptural and the functional. Much like Valentine Schlegel—whom she admires so much she named her 750-liter kiln Valentine!—she creates “living sculptures,” such as a bench shaped like a reclining woman: “The idea came from a woman napping on a bench. I love curves—I want them to feel sensual!”

For the lines, which she wants “tense and effective,” she refines her forms with a wood saw. She works alone, or almost: “My partner and my father help with heavy lifting, but I want to buy equipment to become fully autonomous—like an electric stacker so I can load the really large pieces into the kiln myself.” So, taking on an assistant is out of the question, no matter how successful her mirrors and partition-sculptures become. “I enjoy working on a human scale—my scale. My studio is a refuge, a cocoon, where I need to be alone. Besides, I have no desire to overproduce. The planet is cluttered enough with objects!”