Natasha Dakhli doesn’t particularly enjoy talking about herself. When I call her one summer evening for this interview, she almost immediately tells me she’s worried she might ramble, lose focus, or say too much. The exercise unsettles her a little, but she plays along with sincerity. She feared digressions, yet that’s exactly what makes the conversation so precious. We had planned to speak for thirty minutes. We ended up talking for an hour and a half. Not because Natasha meanders, no. But because she chooses her words carefully, wanting them to land just right. Just like in her practice, she explains, revisits, steps back, rephrases, always striving for precision. And it’s through this attention to clarity that she lets us in: into the intimacy of her work, her imagination, her sense of longing. Since 2022, Galerie Mélissa Paul has collaborated with this young French artist, fresh out of the Maison de la Céramique. Her work impresses with its visual strength. But perhaps it’s her quiet gentleness, this pursuit of a certain kind of justness that’s more felt than understood, that leaves a lasting mark.

— By Feriel Rahli. For UNFOLD Issue #1, July 2025.

Hi Natasha, thanks for taking the time to talk. I know your days are busy, what are you working on at the moment?

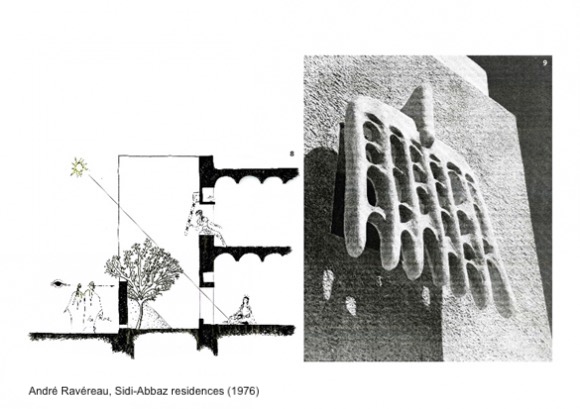

Right now, I’m shaping new pieces for the 40th edition of the European Ceramics Festival in Saint Quentin-la-Poterie, where I’ve been given free rein. I’m exploring forms inspired by ventilation systems in Berber architecture: how air currents, light and shade were designed to cool buildings naturally, to create protection, privacy… It’s fascinating. The habitat is designed according to the rythms of the sun in order to provide shade, to let the light of the moon and and the wind through, to allow the inhabitants, particularly the women, to see without being seen. This architectural intelligence speaks to me deeply. I’m drawing on it to create a series that brings this way of inhabiting the world into focus.

Natasha Dakhli's studio in Saint-Victor-La-Costes.

« I’m exploring forms inspired by ventilation systems in Berber architecture: how air currents, light and shade were designed to cool buildings naturally, to create protection, privacy… »

— Natasha Dakhli.

« I love the idea of my pieces being part of an architectural whole. That said, I don’t want to choose between making pure sculpture and giving an object a function. I think the two can speak to each other. »

— Natasha Dakhli.

So how does a piece come to life? At what point do you feel it’s finished?

My process is always the same. I start from something that inspires me: a picture in a book, a line in a film, a curve I’ve spotted somewhere. I’ll keep that shape or trace in mind, and then I create clay mock-ups in the studio. I can spend entire phases of several days doing only that.

The mock-up helps me think through how the piece will be built, the steps, the structure. Where do I need to reinforce? Where do I need to lighten? It’s also where I make mistakes, it’s better there than when I’m building the actual piece, especially since my work tends to be quite large.

Then I step back, revisit, refine, test the limits of that inspiration. Once I’m satisfied with the mock-up, I begin the final piece. It’s a very instinctive process. There’s a moment when I feel it physically, that the shape is just right.

I spend a lot of time looking at the piece, stepping back. At first I needed someone else’s eye, my partner’s. But now I trust myself more.

You grew up between Berber and Mediterranean cultures. What inspires you from that heritage, and how does it resonate today in your life in the South of France?

My mother is French, my father Algerian. I grew up in a kind of cultural in-between, surrounded by very different influences. On the Algerian side, integration was a priority, so culture was passed on indirectly.

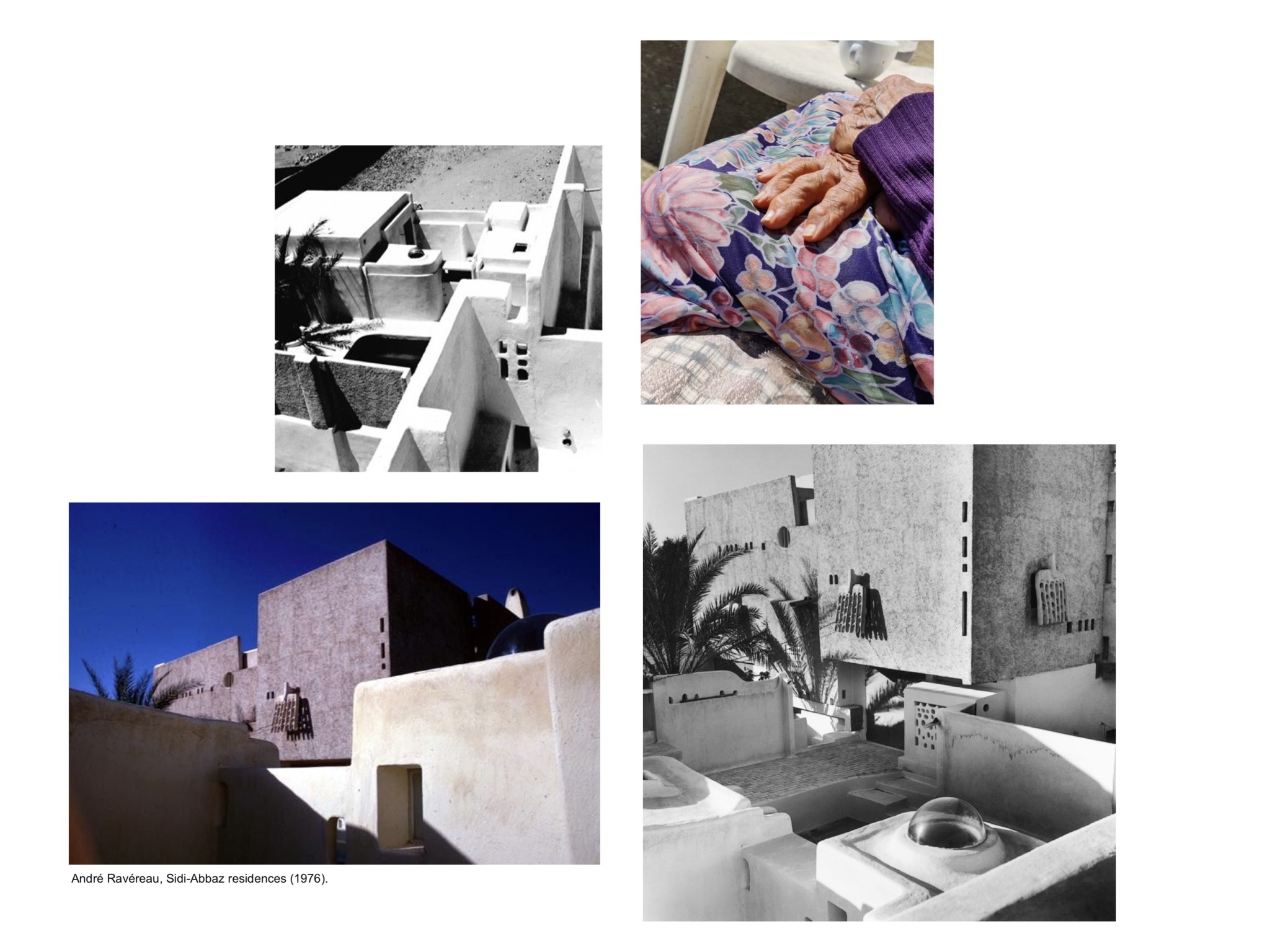

Sadly, I’ve never been to Algeria. But I’ve built a rich imaginary world from the stories I’ve heard, the things I’ve read, searched for, fantasised about. What stays with me are vivid images: the architecture of my grandparents’ home, the way my grandmother spoke, the tattoos on their hands.

It may not be accurate, but it’s become a kind of inner memory. I often think of the village of Morsott, near Tébessa. I would have loved to go for my thirtieth birthday. It’s still a dream.

You’ve mentioned your grandparents’ home and architectural inspiration, and you’ve described before your work as being somewhere between ritual and domestic space. How does that manifest in your practice?

I love the idea of my pieces being part of an architectural whole. That said, I don’t want to choose between making pure sculpture and giving an object a function. I think the two can speak to each other.

I like the idea that my pieces can be touched, used, that they blend into a space, whether indoors or outdoors. I want them to become part of people’s everyday lives, to live with them and adapt to how they move through the world.

Your work plays with contrast: texture, light, emptiness, volume. Where does that sensitivity come from?

Before I discovered clay, I painted for years. As a teenager, I studied with Christian Parra, a painter who taught me a lot about line and abstract composition.

I remember making abstract pieces based on still lifes, where I’d add or remove lines until the subject was only barely visible. The aim was always to find that point where the composition felt right. That’s something I’ve kept with me when working on my mock-ups.

It’s really important to me that the composition is just right. I love playing with edges, lines, curves. I want there to always be movement. I like the contrast between an efficient line, which can appear strict, and the roundness that softens it. It reminds us of the body, of life. That’s exactly what I find in Berber architecture: a geometric rigour mixed with a sensuality, a simplicity of volumes. It moves me deeply.

Ceramics requires a slow pace, patience, observation. How do you relate to that rhythm?

People often tell me I’m slow, and I think that pace suits me. Everything takes time in ceramics: shaping, drying, especially for larger pieces, glazing, firing…

I fire with gas, sometimes for ten hours, checking every thirty minutes. The rhythm is a bit paradoxical: I can spend several days on one step, and yet I never do the same thing twice.

Do you have a favorite step in the whole process?

I think the stage I like the most is at the end of the shaping, when the piece has started to dry slightly but is still damp. We call this stage the « leather texture », it’s like a chocolate consistency. I like the sheen that comes off the piece at this point, it’s time for the final touches.

Which piece has surprised you the most in your career?

The moucharabieh I made for my diploma at the Maison de la Céramique. It was a piece I’d had in mind from the start of my training, but I’d never dared make it before. I was mainly throwing on the wheel back then. I’d only just begun learning hand-building, and I still felt like a beginner.

And having an idea in your head is one thing. Bringing it to life, especially at that scale, is something else entirely. Also, I worked with my father, who used to work in metal, to design the iron framework. And did everything, the moulds, the modules, all of it. There were 21 pieces to assemble, and I only saw it put together the day before my final presentation.

That piece made me proud. Seeing everything I’d built, and realising I was capable of it. It was emotional. And it changed everything. Two months after finishing my training, Mélissa Paul reached out after seeing that piece. Three years later, I’m still building on what it made possible.

Now I feel like I’m at another turning point with the pieces I’m currently working on. I’m freeing myself, and allowing a more intuitive approach to emerge. I’m hand-building without moulds. I feel closer to what I really want to express. It’s a continuation of what I’ve done before, but in a new register. Still a moucharabieh, but these pieces feel more like me than ever.

Is there an object you’ve always dreamed of creating?

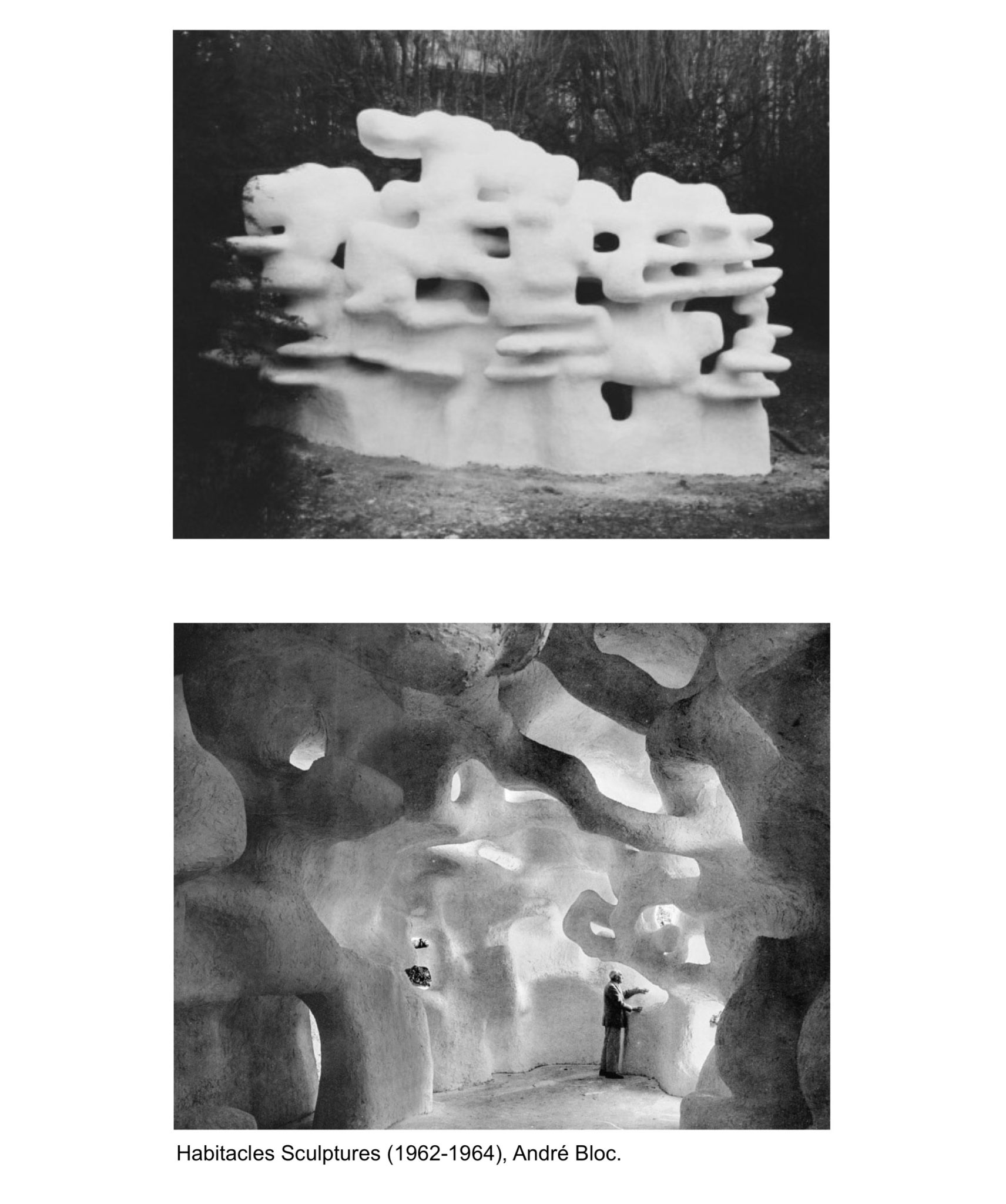

That’s a tough one, but right now I’m thinking of a piece by André Bloc. He was an architect, sculptor, publisher… a complete artist. What I admire in him is his ability to let disciplines blend and speak to each other.

I’m thinking of his “habitable sculptures”, like the one he built in his garden in Meudon. It’s abstract, monumental architecture, not meant to be lived in, but borrowing the codes: walls, openings, a roof… though nothing inside is straight.

I find that work deeply moving, both visually and conceptually. It reminds me of troglodyte dwellings, hand-shaped forms, weathered by time. He later rebuilt it in brick and lime-coated concrete.

It’s an extraordinary piece. I would have loved to make something like that: a sculpture on a human scale, between architecture and art, rooted in a landscape and an imaginary.

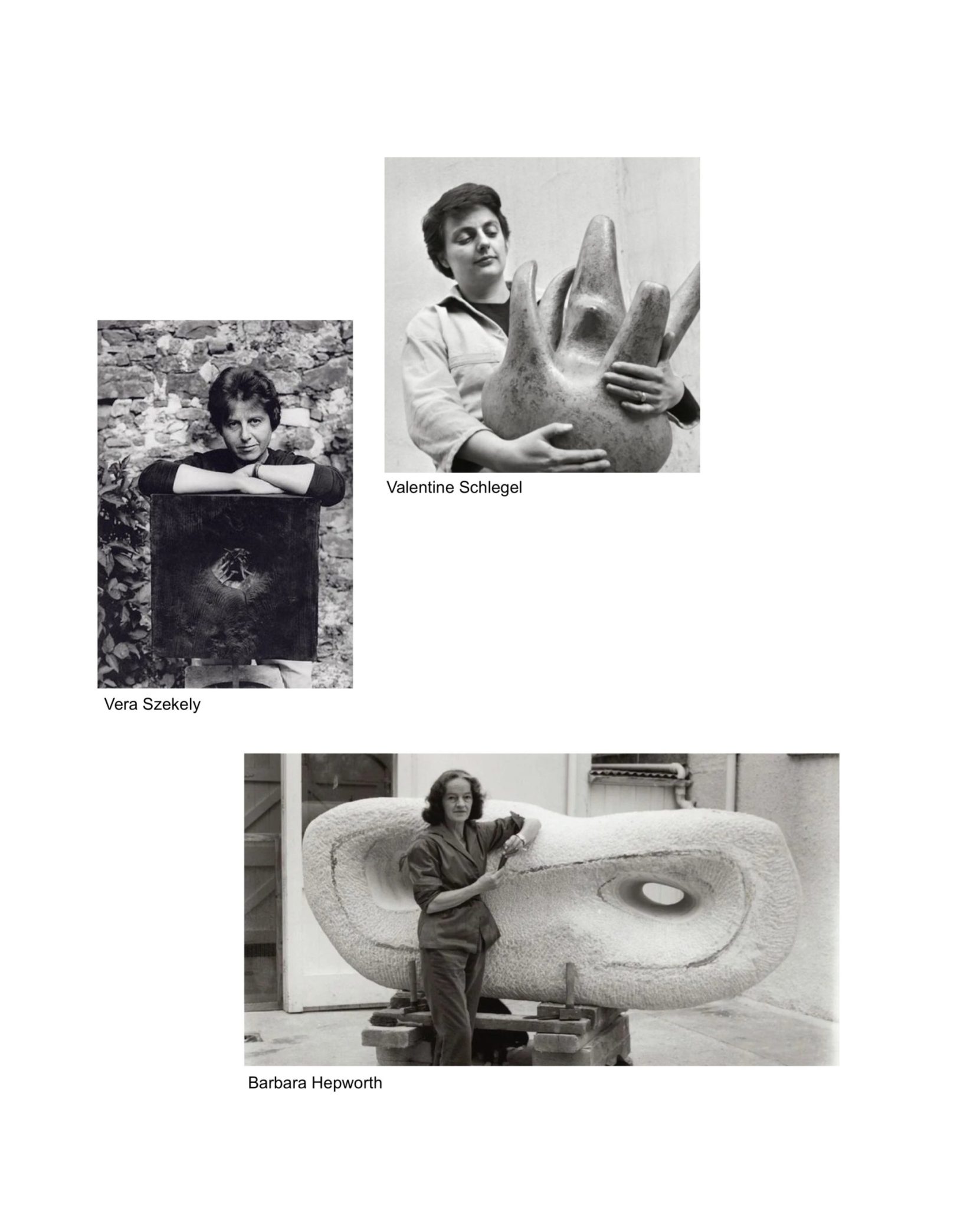

We’ve heard you named your kiln « Valentine », after Valentine Schlegel. Are there other artists or ceramicists who inspire you daily?

Yes, so many! Alicia Penalba, Vera Szekely, Elisabeth Joulia, Gisele Buthod-Garçon… and of course Barbara Hepworth. I want to name only women, that feels important.

These are the names that come to mind first.

Is there a question you wish people asked more often about your practice?

I’d love to know what conditions artists create in! What they listen to, or don’t.

That’s such a good question. Can I steal it? So what do you listen to when you work?

I’m naturally anxious, so I find silence hard. I listen to a lot of podcasts, mostly feminist ones. l’ve got a little routine: France Inter in the morning, then podcasts in the afternoon, sometimes a bit of music, but that’s rarer.

And finally… what can we wish you for the future?

That it keeps going! And more collaborations. Even though I love the solitude of the studio, I also really enjoy breaking it now and then, through exhibitions, fairs, conversations.

I love collaborating with artists. I recently worked with my friend Léna Morelli, a paper artist from my area. I’d love to do more projects like that, with photographers, people in fashion, architects… And of course, with gallerists too, that’s a form of collaboration I value deeply.

And most of all… wish me a trip to Algeria!